How (and Why) to Read Memoir

A missive on the genre, systemic dysfunction in publishing, and what makes a story good

Interested in reading memoir? First you’ll have to find it. Memoirs defy existing bookstore classifications. They’re tucked in biography and subject-specific nonfiction shelves. Sometimes they’re categorized as autobiography—a label that’s close, but not quite. Most people have a general idea of what memoir is, but can’t put their finger on exactly what it is. The current situation among many well-intentioned readers is akin to my kid pondering his birth and breastfeeding doll. But Mommy, where DOES the baby come out? The butt? Close, but not quite.

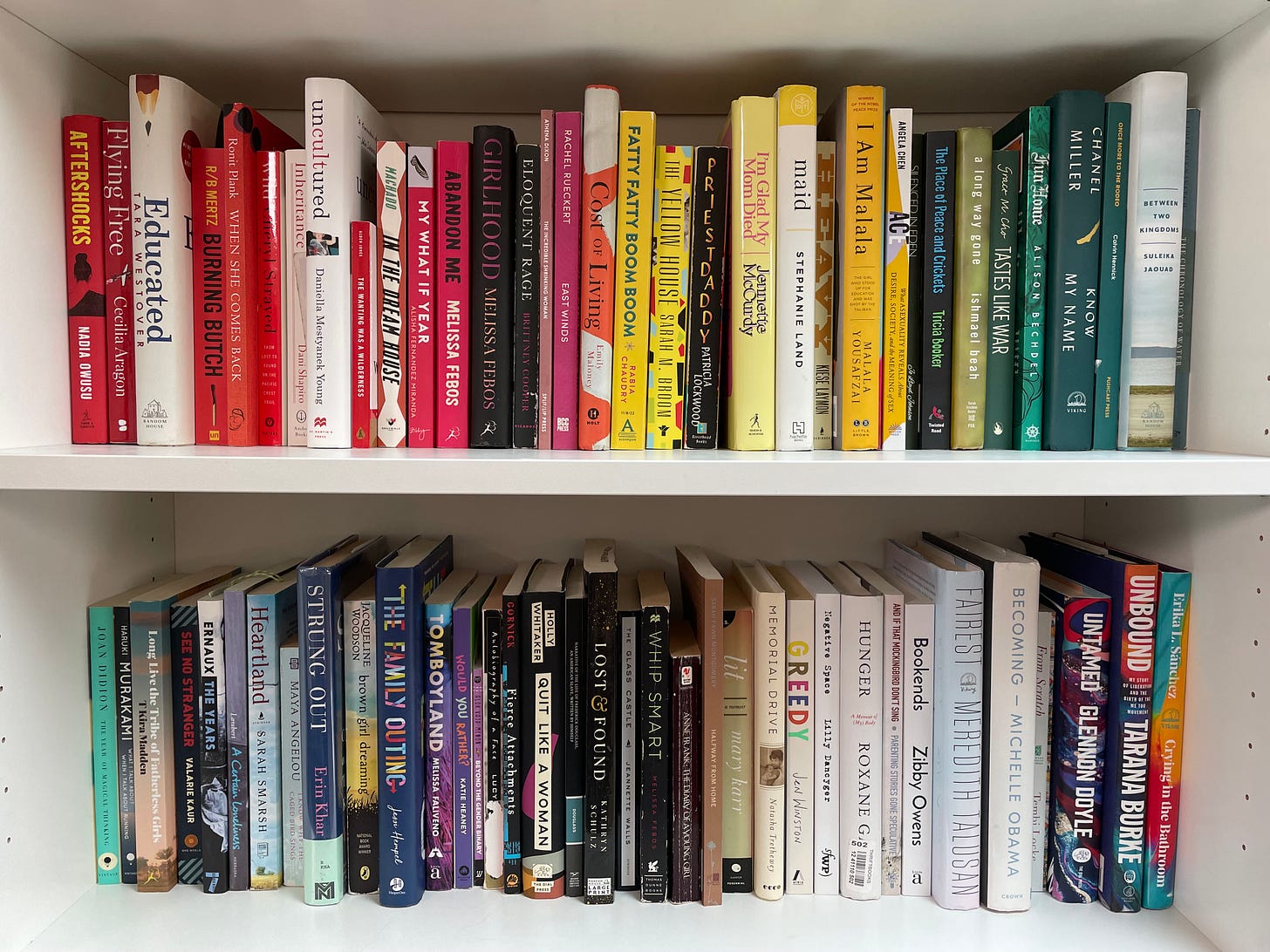

Contrary to popular conception, memoir doesn’t only consist of books that begin with First, I was born and dovetail into Last, I died. The type of memoirs I can’t get enough of are the ones featuring excerpts of a person’s life, organized around a central theme. Some of the more well-known examples you may have read are Elizabeth Gilbert’s travel memoir Eat, Pray, Love and Tara Westover’s coming-of-age memoir Educated. Westover’s debut memoir was one of the top-selling memoirs in recent years (more than 6 million copies sold as of 2020), second only to Michelle Obama’s Becoming, an excellent read which may also be considered more of an autobiography than the type of memoir I’m introducing here.

It’s not fair to entirely blame bookstores for the current invisibility of memoir. The problem, like so many others, is systemic. Bookstore owners typically shelve books according to their BISAC codes, a hierarchy for classifying publications where Personal Memoir is tucked under Biography & Autobiography. Memoir escapes that primary level of categorization, and as Rebecca Solnit writes in Men Explain Things to Me, “What escapes categorization can escape detection all together.”

Even if you know what you’re looking for and where to find it, many of the best memoirs never make it into readers’ hands. In addition to their invisibility and historically maligned reputation in a white male-dominated literary world, memoirs—like all genres—fall victim to the inherent dysfunction in the publishing system. What makes the difference between a best-selling book and a midlist book? Usually, it’s the resources a publisher decides to put into promoting the book. How do they decide which books to promote? Typically, it’s the books that tell stories similar to ones that have been told before and have sold well. It’s a snowball of a setup that rarely makes room for new and untold stories. Writers know this as the tyranny of comps. If there’s nothing to compare your book to, there’s no proven audience. The barriers to entry in publishing are colossal, especially for authors of marginalized and underrepresented identities.

Melissa Febos summarizes the situation in Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative when she writes “Just as the justice system was not designed to protect or enact justice for all (and often was designed to protect those with the most power from their harms against those with less), the values of literary publishing were not designed to support or promote all stories.”

The current push for diversity in publishing, however well-meaning or not, is not enough. Elaine Castillo highlights in her recent book How to Read Now that authors of color in fiction are being forced to show up in prescribed ways that meet consumer demand. In layman’s terms, only certain types of stories, told in certain types of ways, get published and earn money. In theory, this should be happening less in memoir, where authors tell their own stories on their own terms. In reality, movements like Own Voices have forced authors into disclosing identities prematurely or in unsafe situations in order to validate and sell their stories. According to publishers and book sales, this is what the current book market is demanding. Readers—especially white people like me—are seeking education and tools for empathy, which often leads us to take lazy shortcuts in what we read and what we do with what we read. “The result,” writes Castillo, “is that we largely end up going to writers of color to learn the specific—and go to white writers to feel the universal.” Readers, we can do better than this.

I can do better. As a humble next step in the right direction, might I suggest we find and read memoir more widely? I started reading memoir because I wanted to write memoir. But reading memoir, even more than making me a better writer, is making me a better human—one who is interested in knowing the world and the people in it. One who is casting off false identities and moving into more authentic ways of being. One who believes every person under the sun has a story to tell that I need to hear. One who is willing to reconsider what makes a story good.

This last consideration leads me to this memoir missive’s final frontier: the literary critique. Reviews in coveted spaces like the New York Times and the LA Review of Books have the potential to make or break a book’s sales. Many work out well for the author. Others have the effect of dissecting a work to death. Some stoop to critiquing the life decisions of memoirists rather than their story and why they’re telling it. Still more exist only because the author or their publisher can afford to pay the publication for a review. If a book doesn’t get a review, it’s as invisible as a misshelved memoir in a bookstore.

There has to be a better way to take the pulse of a person’s lived experience. The closest I’ve come to seeing an alternative articulated is in Men Explain Things to Me by Rebecca Solnit. On page 93, she writes:

There is a kind of counter-criticism that seeks to expand the work of art, by connecting it, opening up its meanings, inviting in the possibilities. A great work of criticism can liberate a work of art, to be seen fully, to remain alive, to engage in a conversation that will not ever end but will instead keep feeding the imagination. Not against interpretation, but against confinement, against the killing of the spirit. Such criticism is itself great art.

As I embark on this new project, Memoirs with Melissa, I can’t pledge to get everything right or rise to the level of great art, but I can promise that every review I post here is intended to lift up the memoir, its author, and their call to action. Any memoir I write about, I’ve read (or listened to) and considered deeply. I thrive on symbolism, unconventional thinking, stories that blow the gender binary to pieces, and ideas that shake up my understanding of the world. I seek diversity in authors, story structures, book length/age, and ways of publishing. I find them through social media, writing conferences, libraries, used bookstores, and coincidental meetings in my daily life. However they enter my personal bookshelf, I’m eager to engage in conversation with just about any memoir and the person behind it.

Forget the literary canon. This is the canon of human experience, and I am here for it all.

I can so relate to that urgency. There are so many stories, and I want to osmosis them into my brain. It's taking discipline to slow down and give the intimacy of each story the time and space it deserves. Thanks for reading, Rona!

Reading memoir, I am keenly aware that a real human lived this story and met the challenge of bringing it to the world, often in the face of resistance from within and without. Memoir has an intimacy and urgency that pull me back again and again, as a reader and a writer.